Since writing last week about Hepzibah Swan's

French-inspired pavilion in Dorchester, Massachusetts, I've been thinking about curves and ovals in Federal architecture.

|

| The 1772 version of Monticello is outlined in bold. |

Although American architecture had started breaking out of the square box as early as 1772, when Thomas Jefferson designed an octagonal bayed pavilion as the first house at Monticello, the movement toward more innovative room shapes did not begin in earnest until after the Revolution.

In 1788, William Hamilton built a house in Philadelphia with the earliest known surviving oval rooms in America, in a complex plan probably derived from an English pattern book. The curve and the octagon did not fully enter the American design vocabulary until 1792, when James Hoban won the competition to design the new President's house in Washington, with its garden room centered on an oval bay fronting three oval rooms, each above the other.

|

| James Hoban's plan for the President's House, the beginning of a vogue for houses with oval bays at center, after the English fashion. |

|

The new fashion traveled quickly through the major cities, but nowhere did it gain foothold than the Boston area, where many country houses, beginning with Charles Bulfinch's Joseph Barrell mansion in Charlestown, in 1792.

|

| Charles Bulfinch's drawing for the Joseph Barrell house in Charlestown, with portico above and oval salon. (For a 1920's adaptation of this design in the Stotesbury cottage at Bar Harbor, click HERE) |

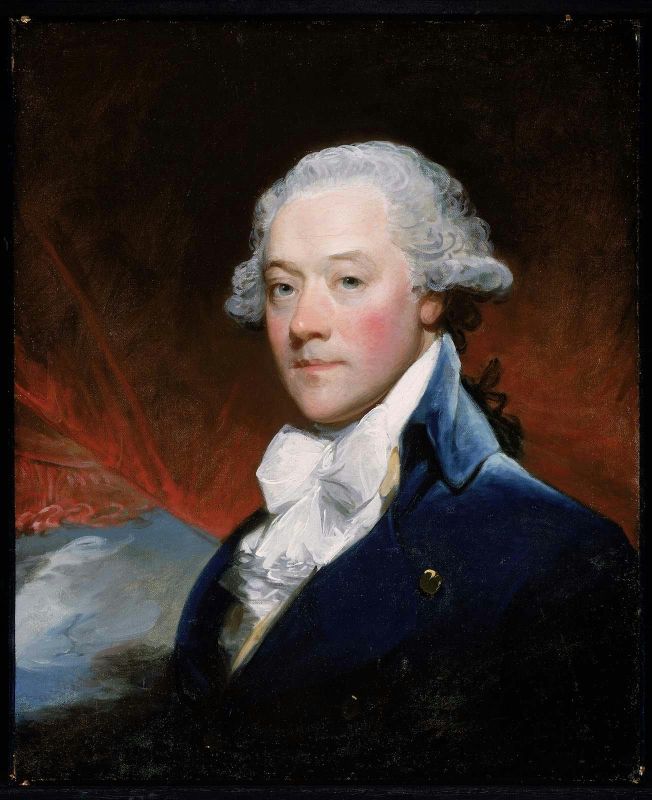

These houses were built by the city's new plutocracy, the men and women who had come to prominence during the revolution, and the early years of the Republic. Their portraits were painted by Gilbert Stuart, their houses were often designed by Charles Bulfinch, and they led the stylish aspirations of their day.

|

| The Jonathan Mason house on Beacon Hill, designed by Bulfinch, and likely the first of the hundreds of bow front townhouses that defined domestic building in Boston for the next century. This house survived only a few years after construction, torn down when Beacon Hill was lowered. |

Within the next decade, at least a dozen houses with garden facades centered on a curved or octagonal bay were built in the countryside around the city, and in town, the bow front brick town house, first introduced by Bulfinch, became the most enduring architectural symbol of the city.

|

| Perez Morton, by Saint-Memin |

|

| Mrs. Perez Morton (1759-1846) by Gilbert Stuart, 1802 (MFA, Boston) |

It was against this background that Mr. & Mrs. Perez Morton, he a lawyer, she a descendant of one of Boston's most distinguished families, the Apthorps, built their country house in Dorchester, practically across the street from the Swan's fashionable concoction.

Although under construction at the same time as the Swan house, the Morton house was less fashion forward than the former, its facade centered on pairs of engaged pilasters supporting a traditional pediment.

|

| The Perez Morton house, Dorchester, MA, 1796 |

|

| The Stable complex |

To the side was an extraordinary complex of stables and outbuildings, all adjoining---the ultimate example of the famous New England paradigm of 'big house, little house, back house, and barn', in which all services are connected under cover, from main house to privy to stable to wood house, that one might not have to brave snows and drifts to attend to the various functions of life. In this, the New England houses may be thought to have a direct link to the Italian farm villas.

|

| Morton house, garden facade prior to demolition |

At the rear, an octagonal bay projected from the house, containing both an oval salon with a chimney piece imported from France, and an upper veranda, a simpler echo of the upper portico at the Barrell house.

|

| Another portrait of Mrs. Morton by Gilbert Stuart (Worcester Art Museum |

The Morton house is sometimes attributed to Charles Bufinch, who was Mrs. Morton's cousin, and he may well have advised, but Mrs. Morton herself wrote that the house was designed to her own 'whimsical plan'. Sarah Wentworth Apthorp Morton was a woman of considerable talents. Well educated, she wrote verse as a child, and in 1789, at the age of 30, she began contributing to the 'Seat of Muses' in Massachusetts Magazine. Her books of verses came to include Ouâbi: or the Virtues of Nature. An Indian Tale in Four Cantos, 1790, and The Virtues of Society. A Tale Founded on Fact, 1799, as well as an anti-slavery poem, The African Chief. Mr. Morton, like his exiled neighbor across the street, appears to have had a caddish streak, and had an affair with his sister-in-law, which did not end well.

|

| Stair hall in the Morton house. The placement of the stair in a side hall off a long main hall was less usual in New England than the mid-Atlantic or Southern States. |

The interiors of the Morton house featured elaborate Adamesque plasterwork ceilings, a relative rarity in the United States. The slightly awkward oval room featured a coved ceiling, also unusual, and a less sophisticated echo of the Swan's domed circular room across the street. According to early accounts, the friezes over the doors featured swags centered by American eagles and shields, a first floor room in the octagonal bay had Zuber scenic wallpaper, and the 'sky parlor' in the attic monitor was a room about 10 x 16 feet, with corner fireplace with delft tiles, and windows on four sides looking out to the gilded dome of the State House Boston and the harbor and bay beyond, all now gone.

|

| The oval salon in the Morton house. (From Some Old Dorchester Houses, 1890, via Dorchester Athenaeum) |

|

| The drawing room was on the second floor, unusual for a New England country house. It is seen here prior to demolition in the late 1800s. |

|

| A French window, also unusual in America in the 18th century, opened from drawing room onto the upper veranda. (Some Old Dorchester Houses) |

As he did with the Swan's house, Ogden Codman later mined the Perez Morton house for inspiration for one of his designs in Newport, this time for his cousin, Miss Martha Codman. Miss Codman's house, Berkeley Villa, was an amalgam of several iconic American houses around Roxbury and Dorchester. The entrance facade was based on the Crafts house designed by Peter Banner in Roxbury.

|

| Berkeley Villa, Newport Rhode Island, designed by Ogden Codman, 1910 (NYSD) |

|

| The Crafts house, Roxbury, Massachussets, 1807, as drawn by Ogden Codman, 1892 |

|

| Shirley Place, Roxbury, Massachusetts, as it appeared in the 19th century. Notice dormer configuration later adapted at Berkeley Villa. (Boston Public Library, Department of Prints & Drawings) |

As Berkeley villa was much larger than its model, and required an attic story for servant's rooms, a steeper roof line was based on Shirley Place, the surviving Royal governor's mansion, also in Roxbury, both drawn by Codman as part of his study of early American houses in the 1890s.

|

| Garden facade of Berkeley Villa, inspired by the Morton House |

For the garden facade of Miss Codman's house, the octagonal bay and porch of the Morton house were copied. Charming though the 'authentic' Federal style facade might have been, this house was in Newport, after all, and for the interiors, Codman abandoned the simplicity of late 18th century America in favor of Robert Adam's England, inserting a rotunda stair hall in the center of the house.

|

| Stair Hall at Berkeley Villa (Andy Ryan, New York Times) |

In 1928 Miss Codman married Maxim Karolik a Russian opera singer, and together they formed one of the finest collections of American furniture, with which they furnished Berkeley Villa. That collection is now a cornerstone of the American decorative arts collection at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, where of course, also resides the French furniture brought back by James Swan years earlier.

|

| Sofa by Samuel McIntire and painted side chair once belonging to Elias Hasket Derby, both from the collection of M&M Karolik, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

These blog posts are, as much as anything, just me thinking out loud about things that intrigue me, and making connections. I could go on and mention the garden house (click HERE) designed by Fiske Kimball in 1922 in the grounds of Berkeley villa, that copied one designed by McIntire at Elias Hasket Derby's country estate, and that Kimball in turn was the man who first wrote about Thomas Jefferson's architectural life, as author of the seminal book on McIntire, and that Kimball in turn lived for a time, as director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in Lemon Hill, a house built in 1800, with central bow and oval rooms, or I could just go make lunch.